Nineveh , ancient city, capital of the Assyrian Empire, on the Tigris River opposite the site of modern Mosul, Iraq. A shaft dug at Nineveh has yielded a pottery sequence that can be equated with the earliest cultural development in N Mesopotamia. The old capital, Assur, was replaced by Calah, which seems to have been replaced by Nineveh. Nineveh was thereafter generally the capital, although Sargon built Dur Sharrukin (Khorsabad) as his capital. Nineveh reached its full glory under Sennaherib and Assurbanipal . It continued to be the leader of the ancient world until it fell to a coalition of Babylonians, Medes, and Scythians in 612 BC and the Assyrian Empire came to an end. Excavations, begun in the middle of the 19th cent., have revealed an Assyrian city wall with a perimeter of c.7.5 mi (12 km). The palaces of Sennacherib and Assurbanipal, containing magnificent sculptures, have been discovered, as well as Assurbanipal's library, including over 20,000 cuneiform tablets. The city is mentioned often in the Bible.

Biblical Nineveh

In the Bible, Nineveh is first mentioned in Gen. 10:11, which is rendered in the Revised Version, "He [i.e., Nimrod] went forth into Assyria and built Nineveh."

It is not again noticed till the days of Jonah, when it is described (Jonah 3:3ff; 4:11) as an "exceeding great city of three days' journey", i.e., probably in circuit. This would give a circumference of about 100 km (60 miles). At the four corners of an irregular quadrangle are the ruins of Koyunjik, Nimrud, Karamless and Khorsabad. These four great masses of ruins, with the whole area included within the parallelogram they form by lines drawn from the one to the other, are generally regarded as composing the whole ruins of Nineveh.

Nineveh is the flourishing capital of the Assyrian empire (2 Kings 19:36; Isa. 37:37). The book of the prophet Nahum is almost exclusively taken up with prophetic denunciations against this city. Its ruin and utter desolation are foretold (Nah.1:14; 3:19, etc.). Its end was strange, sudden, tragic. (Nah. 2:6-11) According to the Bible, it was God's doing, his judgement on Assyria's pride (Isa. 10:5-19). In fulfillment of prophecy, God made "an utter end of the place". It became a "desolation". Zephaniah also (2:13-15) predicts its destruction along with the fall of the empire of which it was the capital.

From this time there is no mention of it in Scripture till its exemplary pride and fall are recalled in the Gospel of Matthew (12:41) and the Gospel of Luke (11:32).

History

Nineveh is mentioned about 1800 BC as a worship place of Ishtar, who was responsible for the city's early importance. There is no large body of evidence to show that Assyrian monarchs built at all extensively in Nineveh during the 2nd millennium BC. When Sennacherib made the city of Ninua his capital at the end of the 8th century BC, it was already an ancient settlement. Later monarchs whose inscriptions have appeared on the Acropolis include Shalmaneser I and Tiglath-Pileser I, both of whom were active builders in Ashur; the former had founded Calah (Nimrud). Nineveh had to wait for the neo-Assyrians, particularly from the time of Ashurnasirpal II (ruled 883-859 BC) onward, for a considerable architectural expansion. Thereafter successive monarchs kept in repair and founded new palaces, temples to Sin, Nergal, Nanna, Shamash, Ishtar, and Nabu of Borsippa.

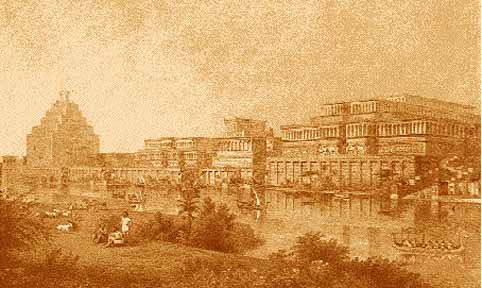

It was Sennacherib who made Nineveh a truly magnificent city (c. 700 BC). He laid out fresh streets and squares and built within it the famous "palace without a rival", the plan of which has been mostly recovered and has overall dimensions of about 210 by 200 m (630 by 600 ft). It comprised at least 80 rooms, of which many were lined with sculpture. A large part of tablets was found there; some of the principal doorways were flanked by human-headed bulls. At this time the total area of Nineveh comprised about 1,800 acres (7 kmē), and 15 great gates penetrated its walls. An elaborate system of 18 canals brought water from the hills to Nineveh, and several sections of a magnificently constructed aqueduct erected by the same monarch were discovered at Jerwan, about 40 km (25 miles) distant.

Nineveh's greatness was short-lived. About 633 BC the Assyrian empire began to show signs of weakness, and Nineveh was attacked by the Medes, who subsequently, about 625 BC, being joined by the Babylonians and Susianians, again attacked it. Nineveh fell in 612 BC, and was razed to the ground. The Assyrian empire then came to an end, the Medes and Babylonians dividing its provinces between them.

After having ruled for more than six hundred years with hideous tyranny and violence, from the Caucasus and the Caspian to the Persian Gulf, and from beyond the Tigris to Asia Minor and Egypt, the city vanished like a dream.

Before the excavations in the 1800s, our knowledge of the great Assyrian empire and of its magnificent capital was almost wholly a blank. Vague memories had indeed survived of its power and greatness, but very little was definitely known about it. Other cities which had perished, as Palmyra, Persepolis, and Thebes, had left ruins to mark their sites and tell of their former greatness; but of this city, imperial Nineveh, not a single vestige seemed to remain, and the very place on which it had stood was only matter of conjecture.

In the days of the Greek historian Herodotus, 400 BC, it had become a thing of the past; and when Xenophon the historian passed the place in the Retreat of the Ten Thousand the very memory of its name had been lost. It was buried out of sight, and no one knew its grave. It is never again to rise from its ruins.